For the 2018 election cycle, NLIHC’s Our Homes, Our Votes nonpartisan voter engagement project tracked the major local and state ballot measures for affordable housing revenue and tenant protections across the country. There were some big wins for affordable housing advocates—and some narrow losses. The success of the initiatives that passed show strong support from voters for addressing the lack of affordable housing in their states.

There were two major types of affordable housing ballot measures up for a vote this past election cycle- measures that sought to increase funding for affordable homes and measures that sought to increase tenant protections by implementing rent control laws. Out of the 26 ballot measures that sought to expand affordable housing resources, 20 passed. Out of the seven ballot measures that aimed to expand rent control, five passed.

Many of the successful funding ballot measures either increased taxes or created a new tax dedicated to affordable housing. Voters in California supported the creation or increase of a wide variety of taxes. Several ballot initiatives that passed created hotel taxes or increased sales taxes that will dedicate millions of dollars to affordable homes. Voters in San Juan County, Washington supported an additional real estate excise tax which will enable the County to collect .5% of the selling price for county owned real estate.

Voters also passed general obligation bonds to fund affordable homes. General obligation bonds are sold to investors and used to finance public projects. The government that issues the bond is expected to pay it back in full. Seven bond funding ballot measures were passed, including one in Charlotte, North Carolina that will increase the city’s affordable housing trust fund from $15 million to $50 million.

Voters in Idaho, Nebraska and Utah all overwhelmingly passed measures to expand Medicaid coverage to all low-income adults. Medicaid expansion has been used to fund housing support services such as case management, navigation assistance, and street outreach. Medicaid expansion also covers populations that weren’t previously covered by Medicaid, such as people experiencing homelessness.

The rent control ballot measures that passed in the 2018 elections were limited in scope. Three wards in Chicago, Illinois passed advisory referendums repealing the state rental control preemption law—a law that prevents local governments from passing or enforcing measures that would set rent limits. An advisory referendum means voters let their views be known about an issue without creating any binding legislation.

In Santa Cruz, California, Measure M passed, which will require moving assistance provided for tenants evicted without just cause and limit rent increases in apartments built before 1995. Voters in Berkeley, California approved Measure Q which will allow for newly built properties to have rent control and will prevent land lords from increasing rents in existing rent control units when the units become empty, though implementation of this measure will require the repeal of California’s Costa-Hawkins Act, which forbids rent control on new development. Proposition 10, which would have allowed California communities to move forward with rent control proposals, failed at the polls by a vote of 38% to 62%.

Many states and localities grapple with the affordable housing crisis and seek local policy changes aimed at improving housing affordability. When low-income residents and allies vote for affordable rental housing, the they move the needle. Win or lose, these ballot initiatives represent real movement towards increasing the visibility of the affordable housing crisis.

To view the ballot measure chart visit: https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/Housing-Ballots_Initiatives.pdf

Making Change by Running for Office When the Advocate becomes the Elected Official

Ballot initiatives are not the only way that housing advocates are changing housing policies at the local level. More and more low income residents, allies, and housing professionals are running for public office…and winning! Here are thoughts from a few recent examples of advocates who stepped inside the halls of power and became elected leaders.

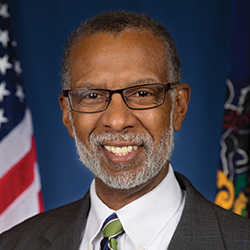

Senator Art Haywood

Senator Art Haywood; Pennsylvania State Senate District 4

Bio: Senator Haywood ran for office for the first time in 2009 after being inspired by President Barack Obama’s successful campaign the year prior. After serving on the Cheltenham Township Board of Commissioners, he won a race for state senate in 2014. Prior to running for office, Senator Haywood’s career as an attorney focused heavily on work to preserve and create affordable housing through positions with Community Legal Services and Regional Housing Legal Services.

What housing achievements are you most proud of while serving in the State Senate?

My biggest and most proud housing achievement was ensuring that there was a permanent revenue source for the state housing trust fund. My district has benefited directly from the investment. Recently, $400,000 was awarded to an organization that provides home repair grants to retirees. Retirees’ incomes have not kept up with inflation. Some of the houses have a lot of deferred maintenance—home owners cannot address roof problems or plumbing breakdowns. The money from the housing trust fund stabilizes neighborhoods and keeps people in their homes. These funds prevent housing vacancies and blight that bring neighborhoods down. I see the direct impact of the housing trust fund in my district every day.

What advice would you give to a housing advocate who wants to run for office?

Elections matter. Over the past three years, the state has allocated over $15 Million in grants for affordable housing projects. I was able to get dollars into my district to stabilize individuals and help people stay in their homes. People take for granted state house and state senate elections, but legislators can have a big influence on policies in their states.

Run and recognize that the first time you run you may not win. It may take two times to win, and that’s okay. We need advocates in decision making positions so that they can be in a place to get more housing funding. Creating a blight elimination program is an example of something a statewide or county wide government can do. It’s good to have people on our side. There will be a legislator for your district and someone is going to fill that position. Why not you? The best way to get important changes passed into law is to be the decision maker.

Mayor Emily Niehaus

Mayor Emily Niehaus; Moab, Utah

Prior to being elected Mayor in November 2017, Emily Niehaus founded Community Rebuilds, a nonprofit devoted to producing affordable and energy-efficient housing. Community Rebuilds includes an emphasis on workforce training through their developments. Emily will remain in a leadership role with Community Rebuilds during her term as Mayor.

The position of mayor is responsible for many issues. Did you find that voters wanted to hear about your ideas for better affordable housing while you were campaigning?

Yes, of course! My three priorities as Mayor are affordable housing, economic diversification, and infrastructure development. Like many other communities, Moab suffers from a lack of affordable housing. The community needs government to step up and work to unlock more housing development opportunities. And, government can play a critical role in the preservation of affordable housing through enabling deed restrictions and creating zoning to exclude short term rentals like Airbnb. I believe that it was the issue of housing and my experience as an affordable housing developer that got me elected.

Did you do any work in your campaign to earn the support of low income renters in Moab?

I did not directly target any one particular group for the campaign. I tried to reach out to everyone. In one mobile home park I visited, I met a veteran concerned about his health care, a single mom unsure if her housing costs were going to go up, a man concerned about water quality and quantity, and a Mexican boy crying because he lost his father, who I believe had been deported. Low income renters have such thick issues. It is our responsibility to listen to them and understand that stable housing is the most critical bridge for getting out of poverty.

What housing affordability solutions do you plan to prioritize now that you are mayor?

Right off the bat, we are 1) hosting workshops to highlight historical issues and efforts to build affordable housing; 2) completing an assured housing analysis and follow through with implementation on ideas such as deed restrictions and employer provided housing; 3) identifying barriers to affordable housing in our City Code; 4) financially support our Housing Authority in project implementation; and 5) creating an incentive program for deed restricted housing development through the creation of the Planned Area Development code.

Council Member Jeremy Schroeder

Council Member Jeremy Schroeder; Minneapolis City Council

Jeremy Schroeder worked as policy director at the Minnesota Housing Partnership (MHP) for nearly two years before his election to the Minneapolis City Council in November 2017. During his time with MHP, Jeremy worked to advance housing affordability at the state level and had significant success working on housing bond legislation with other coalition members. Before working as a professional housing advocate, Jeremy worked on election and campaign finance reforms with Common Cause Minnesota and led the coalition that successfully abolished the death penalty in Illinois.

Did your experience working as policy director for Minnesota Housing Partnership make you a better candidate for Minneapolis City Council?

Absolutely! Our city has an affordable housing crisis to which there is no easy, simple solution. My work as a housing advocate allows me to bring depth to an issue that’s top-of-mind for many Minneapolis residents, which was a huge asset in a competitive campaign where I challenged an incumbent. This also proved to voters that I am well-positioned to cut through the rhetoric and create effective affordable housing policy.

Were there local or neighborhood level housing problems you learned about from voters that had not been a part of your work at the state capitol? How does hearing directly from voters impact your perspective and priorities?

In my work as an advocate, I learned that even when there is a lot of general support for affordable housing, local pushback—mostly to specific projects—is often a huge barrier. Conversations with voters expanded my perspective and showed me that the increased density and affordability needed to make Minneapolis accessible to all, will not be possible unless I clearly explain how those principles will make life better for all of my constituents.

What advice would you give to housing advocates who are considering running for office?

Get involved in local campaigns. Being a housing advocate is a huge advantage given the national conversation around housing, but being a good candidate means having answers for any question that comes your way. You don’t necessarily need the best answer right off the bat, but you need to show that you are aware of the issue and have an opinion about how to address it—especially in policy areas where your opponents are experts. Being an advocate can prepare you to run for office but remember that political campaigns can be very different from advocacy work. Build a solid campaign team that you trust, set a strategy that harnesses your housing expertise and be relentless in your efforts to meaningfully reach every voter in your jurisdiction. It’s never going to be easy, but success is more than possible.