Bushwick Houses

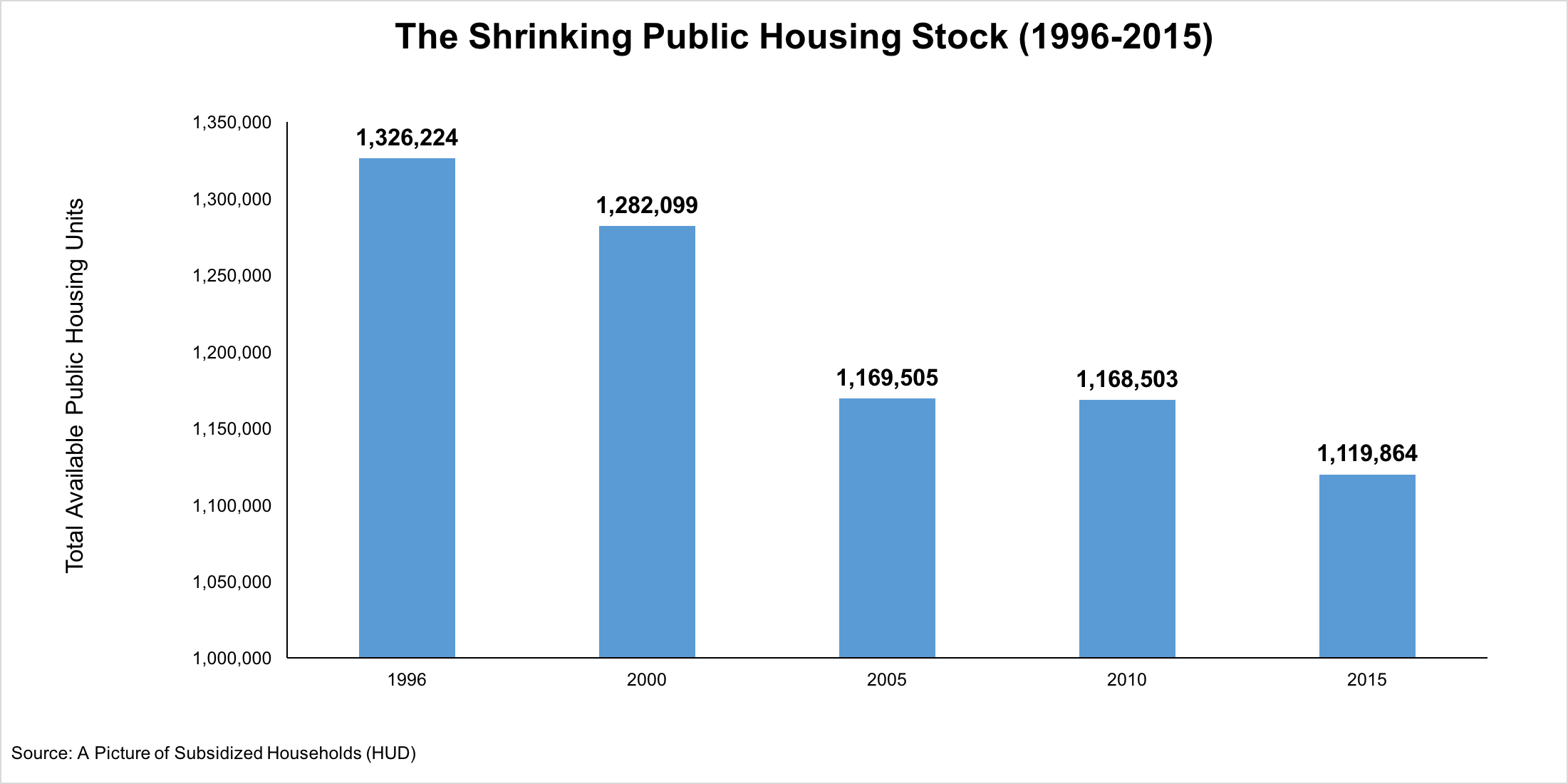

Throughout the nation, public housing is in pretty rough shape. The Public Housing Capital Fund, which Congress provides to pay for repairs, has been underfunded for so long that we now lose more than 10,000 public housing apartments each year because they are no longer habitable. Some public housing agencies have endured financial challenges and mismanagement that leads to HUD taking them over.

The best response to this crisis is for Congress to provide the estimated $70 billion necessary to repair public housing and stop the unnecessary loss of these scarce affordable homes. Congress has been unwilling to do that. Lacking the money needed to make urgent repairs, HUD is turning more and more to alternative solutions that “reposition” public housing to solutions programs that involve private financing and rely on vouchers.

Public Housing ‘Repositioning’

HUD’s Office of Public and Indian Housing (PIH) sent a letter to public housing agency (PHA) executive directors dated November 13, 2018 signaling its intent to remove itself from administering the public housing program. HUD’s immediate goal was to “reposition” 105,000 public housing units by September 30, 2019.

Because Congress has failed to provide adequate appropriations for the Public Housing Capital Fund for many years, there is an approximate $70 billion backlog in capital needs (public housing maintenance and repairs). HUD points to that backlog as the reason to provide PHAs with “additional flexibilities” so they can “reposition” public housing.

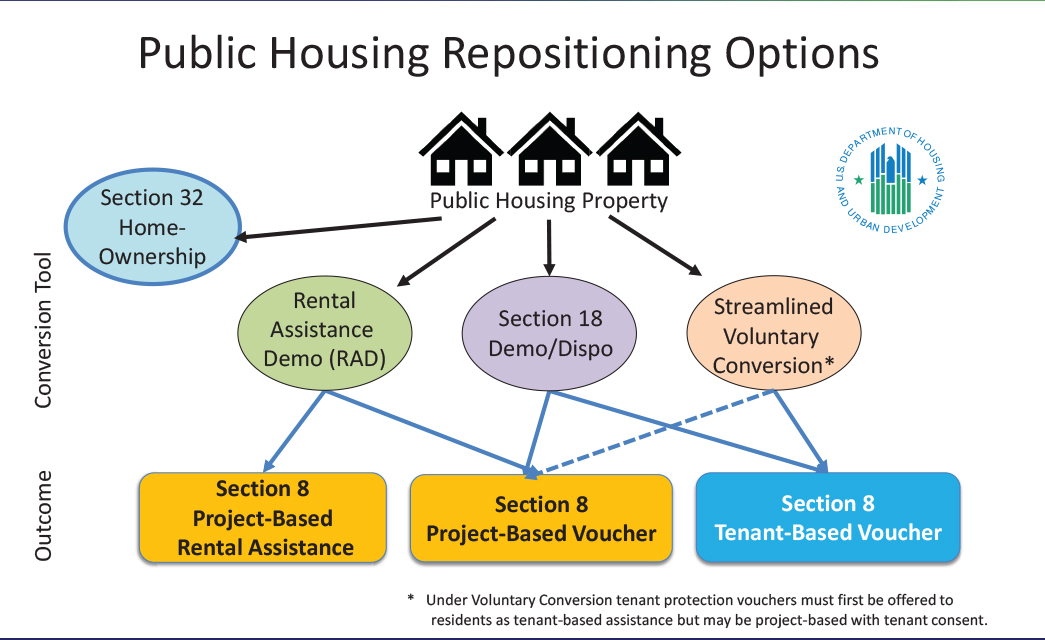

What is “repositioning?” There are three main ways HUD would “reposition” public housing:

- The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)

- Demolishing or disposing of (selling) public housing

- Voluntary conversion of public housing to vouchers

All of these have already been available to PHAs. Repositioning just means making them easier.

Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)

Beginnings

Throughout 2010 and 2011, HUD consulted with public housing resident leaders through the Resident Engagement Group to create a demonstration program that would bring in non-federal resources to address the lack of federal money for public housing maintenance and repairs. HUD also wanted to avoid repeating the mistakes of the HOPE VI program, which resulted in many residents losing their affordable homes. During the planning process, HUD presented three proposals to the resident leaders, and each time the group pointed out a resident-oriented problem. HUD incorporated the feedback from the Resident Engagement Group to create the final proposal, the “Rental Assistance Demonstration” (RAD).

Congress authorized the creation of RAD as part of the fiscal year 2012 HUD appropriations to help preserve and improve low-income housing. RAD does not provide any new federal funds for public housing. There are also no RAD regulations, but RAD conversions must comply with a formal RAD Notice. The current Notice is REV4. (Notice H-2019-09/PIH-2019-23).

What is RAD?

RAD allows PHAs to convert public housing units to either Project-Based Vouchers (PBVs) or Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) – both are forms of project-based Section 8 rental contracts. At first only 60,000 units were to be converted under the “demonstration,” but Congress approved cap increases so that currently 455,000 units can be converted to PBVs or PBRAs. (Both the Obama and Trump administrations have sought to remove the cap and allow all public housing units to convert to RAD; so far that has not happened.) Once converted under RAD, the former public housing’s Capital Fund and Operating Fund are used for PBV or PBRA.

Project-Based Vouchers (PBVs) are Housing Choice Vouchers tied to specific buildings; they do not move with tenants as regular “tenant-based” vouchers do. If public housing units are converted to PBV, the initial contract must be for 15 years (up to 20 years), and must always be renewed. HUD’s Office of Public and Indian Housing (PIH) would continue to oversee the units. Most of the current PBV rules (24 CFR 983) apply.

If units are converted to Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA), the initial contract must be for 20 years and must always be renewed. HUD’s Office of Multifamily Programs would take over monitoring. Most of the current PBRA rules (24 CFR 880 to 886) apply.

Why Might Converting Some Public Housing to Section 8 Be Okay?

Converting some public housing to Section 8 might be necessary because Congress continues to underfund public housing, leading to deteriorating buildings and the loss of units through demolition. Congress is more likely to provide adequate funding for existing Section 8 contracts than for public housing. And, if a long-term rental assistance contract is tied to a property, private institutions might be more willing to lend money for critical building repairs. Therefore, some homes that were public housing before conversion are more likely to remain available and affordable to people with extremely low- and very low-incomes because of long-term Section 8 contracts.

What Are the Resident Protections that the Resident Engagement Group Secured in RAD?

Both the appropriations act and HUD’s formal rules for RAD include all of the protections the Resident Engagement Group (REG) sought. It has been up to residents, however, to try to get HUD, PHAs, developers, and owners to comply.

Displacement. Permanent involuntary displacement of current residents cannot occur. If a household does not want to transition to PBV or PBRA, they may move to other public housing if an appropriate unit is available.

Right to Return. Residents temporarily relocated while rehabilitation happens have a right to return.

Rescreening. Current residents cannot be rescreened.

Tenant Rent. Existing PBV and PBRA rules limit resident rent payment to 30% of income, or a minimum rent, whichever is higher. Any rent increase of 10% or $25 (whichever is greater) due to conversion is phased in over three to five years.

Good Cause Eviction. An owner must renew a resident’s lease, unless there is “good cause” not to – e.g., non-payment of rent, damage to the building, or criminal activity on the property. This protection means that residents cannot be told for no good reason that their lease will not be renewed.

Grievance Process. The RAD law requires tenants to have the same grievance and lease termination rights they had under Section 6 of the Housing Act of 1937. For instance, PHAs must notify residents of the PHA’s reason for a proposed adverse action and of their right to an informal hearing assisted by a resident representative. Advocates argue HUD has not adequately implemented this statutory requirement.

Resident Participation Features

Before a PHA Applies for RAD. The RAD Notice has detailed requirements regarding how a PHA must provide notice to residents. The PHA must hold at least two meetings before applying for RAD and then have at least one meeting after HUD gives preliminary approval (called a CHAP) to convert. Starting with REV4 in September 2019, a fourth meeting is now required after the PHA has a “Concept Call” with HUD. There are also the usual resident, public information, and participation requirements regarding a “Significant Amendment” to a PHA Plan, but those do not kick in until six months after HUD has given preliminary approval and all the project’s financing has been lined up – when the conversion is basically a done deal.

The $25 per Unit for Tenant Participation Remains. Whether a property is converted to PBV or PBRA, the owner must provide $25 per unit annually for resident participation. Of this amount, at least $15 per unit must be provided to any “legitimate resident organization” to be used for resident education, organizing for tenancy issues, and training activities. The PHA may use the remaining $10 for resident-participation activities.

Resident Participation Rights. Residents have the right to establish and operate a resident organization. If a property is converted to PBRA, then the current Section 8 Multifamily program’s “Section 245” resident participation provisions apply.

If a property is converted to PBV, instead of using public housing’s Section 964 provisions, the RAD Notice requires resident participation provisions similar to those of Section 245 used by the Section 8 Multifamily program. For example, PHAs must recognize legitimate resident organizations and allow resident organizers to help residents establish and operate resident organizations. Resident organizers must be allowed to distribute leaflets and post information on bulletin boards, contact residents, help residents participate in the organization’s activities, hold regular meetings, and respond to an owner’s request to increase rents, reduce utility allowances, or make major capital additions.

One-for-One Replacement

Although the RAD Notice does not use the term “one-for-one replacement,” HUD’s informal material says there is one-for-one replacement. But there are exceptions. PHAs can reduce the number of assisted units by up to 5% or 5 units, whichever is greater, without seeking HUD approval. HUD calls this the “de minimus” exception. In addition, RAD does not count against the 5%/5 unit de minimus any unit that has been vacant for two or more years; any reconfigured units, e.g. making two efficiency units into a one-bedroom unit; or, any units converted to use for social services. Consequently, the loss of units can be more than 5%.

What if there is Temporary or Permanent Relocation?

There are separate relocation requirements, Notice H 2016-17/PIH-2016-17, published in 2017.

Temporary Relocation. For moves within the same building or complex, or moves elsewhere for one year or less, the PHA must reimburse residents for out-of-pocket expenses.

If temporary relocation is expected to be for more than one year during renovation, the PHA must offer a resident the choice of temporary or permanent housing and reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses due to the move. Residents must have at least 30 days to decide between temporary and permanent relocation assistance. A PHA cannot use any tactics to pressure residents to give up their right to return or to accept permanent relocation assistance.

Permanent Relocation. If a PHA’s plans for a project would prevent a resident from returning to a RAD project, the resident must be given an opportunity to comment and/or object to the plan. If a resident objects, the PHA must alter the project plans to accommodate the resident in the converted project. If a resident voluntarily agrees to permanent relocation, a PHA must obtain informed, written consent from the resident confirming they agree to end their right to return and acknowledging they will receive permanent relocation assistance.

Additional Relocation Guidance. PHAs or owners must prepare a written relocation plan if temporary relocation is expected to be greater than 12 months or for permanent relocation. Owners must provide a “Notification of Return to the Covered Project” indicating a date or estimated date of return.

Log of Residents Temporarily Relocated. A PHA or owner must create a log listing every household living at a project before it converts. The log must track resident status from temporary relocation through completion of rehab or new construction, including re-occupancy after relocation.

Who Will Own the Converted Properties?

Worries about “privatization.” Theoretically, this potential problem is covered by the RAD statute requiring converted units to be owned or controlled by a public or nonprofit entity. In practice, however, legal services attorneys express concerns about loopholes and recommend PHAs have long-term ground leases that ensure direct control. The RAD Notice provides six ways to meet the “ownership or control” requirement, including a PHA continuing to hold title to the land and any improvements (buildings), or having a ground lease (but not necessarily “long-term”).

If the Project Has Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Financing. A LIHTC property may be owned and controlled by a for-profit, but only if the PHA preserves “sufficient interest” in the property. The RAD Notice lists four ways to meet “sufficient interest.” The two recommended by legal services attorneys are the PHA or its affiliate is the general partner, and/or the PHA continues to own the land and has a long-term ground lease with the owner.

Mixing RAD and “Section 18” Demolition/Disposition

A new wrinkle was added in 2018 when HUD allowed 25% of the units at a RAD project to be “disposed” through “Section 18” of the Housing Act. These units have to be substantially rehabbed or newly constructed and in the “best interest of residents and the PHA.” All RAD relocation and protection requirements must apply to residents of Section 18 units, including resident notice and comment requirements, right to return, no rescreening, and relocation assistance, HUD will not approve a RAD conversion if the Section 18 units would not be replaced one-for-one. The Section 18 units will get Project-Based Vouchers (PBVs). As a result, the project will probably receive more money, making the conversion to RAD more financially feasible.

Choice Mobility

PHAs must provide all residents of converted units the option to move with regular Housing Choice Vouchers (HCVs). For PBV units, the regular PBV rule applies – after one year, a tenant can request a HCV. If a voucher is available, it must be provided; if a voucher is not available, the resident gets priority on the waiting list. For PBRA units, a resident has the right to move after two years with a HCV, if one is available.

Section 3

Although Section 3 applies, a PHA or owner is only obliged to give residents preference for employment and training opportunities tied to RAD-enabled new construction or rehab. Once a project converts, it is no longer subject to Section 3. So residents will not have Section 3 opportunities when jobs previously done by PHA staff arise in the future.

Techwood Homes, The first public housing building, Photo courtesy: Library of Congress

Demolition/Disposition (Demo/Dispo)

Background

Since 1983, HUD has authorized PHAs to apply for permission to demolish or dispose of (sell) public housing units under Section 18 of the Housing Act of 1937. In 1995 Congress ended the requirement that PHAs replace on a one-for-one basis public housing lost through demolition or disposition. In 2016, HUD reported a net loss of more than 139,000 public housing units due to demolition or disposition since 2000.

A PHA must apply to HUD’s Special Applications Center (SAC) to demolish or sell public housing. The application must certify the PHA has described the demo or dispo in its Annual PHA Plan and the description in the application must be identical. Advocates should challenge an application that is significantly different. The information in this article is primarily from the regulations 24 CFR 970.

In 2018, the Trump administration eliminated a 2012 HUD Notice that had modest improvements advocates had suggested. The 2012 Notice served as a reminder to residents, the public, and PHAs of PHAs’ obligations regarding resident involvement and the role of the PHA Plan regarding demo/dispo. The replacement, Notice PIH 2018-04, downplays the role of resident consultation to make demo/dispo easier.

In addition, the Trump administration withdrew proposed regulation changes drafted in 2014 that would have reinforced the modest improvements in the 2012 Notice and required PHAs to submit more detailed justifications for demo/dispo. All of this is a part of the administration’s goal of “repositioning” 105,000 public housing units by September 30, 2019.

Demolition of the Cabrini-Green Homes in Chicago, Joe Flickr, Creative Commons

Resident Participation

A PHA must prepare a demo/dispo application “in consultation” with tenants and any tenant organization at a project, as well as with any PHA-wide tenant organization and the Resident Advisory Board (RAB). The application (form HUD-52860) must include any written comments made by residents, resident organizations, or the RAB, and indicate in writing how the PHA responded to comments. HUD can deny an application if tenants, resident councils, or RABs were not consulted, so residents should challenge an application if they were not consulted or if the consultation was grossly inadequate.

Demolition Applications

Is the Public Housing Obsolete? PHAs must certify that a development is “obsolete,” either physically or in terms of location, and therefore no longer suitable as housing.

Physically obsolete means there are structural deficiencies that cannot be corrected at a reasonable cost. Structural deficiencies can include settlement of floors, severe erosion, and deficiencies in major systems like plumbing, electrical, heating and cooling, roofs, doors, and windows. “Reasonable” cost is defined as less than 62.5% of total development costs for buildings with elevators and 57.14% for other buildings. To show a development is physically obsolete, a PHA must submit a detailed scope of work describing the major systems needing repair or replacement, the need to remove lead-based paint and asbestos hazards, or the need to make accessibility improvements for people with physical impairments.

An obsolete location means the surrounding neighborhood is too deteriorated or has shifted from residential uses to commercial or industrial uses. It can also mean environmental conditions make it unsuitable for residents to live there. “Other factors” that “seriously affect the marketability or usefulness” of the development can also be considered.

“De Minimus” Demolition. PHAs do not have to apply to HUD to demolish fewer than 5 units or 5% of all units over a five-year period. The units being demolished must either be beyond repair or be making room for services such as a child care facility, a laundry room, or a community center.

Disposition Applications

A PHA must certify that keeping the development is not in the best interests of residents or the PHA for one of three reasons:

-

Conditions in the surrounding area (such as commercial or industrial activity) have a negative impact on the health and safety of residents or on the PHA’s operation of the project (which could mean a lack of demand for the units). The PHA would have to show high long-term vacancy rates due to factors such as declining population in the area or a lack of transportation options and community amenities like stores and schools.

-

Sale or transfer of the property will allow the PHA to buy, develop, or rehab other properties that can be more efficiently operated as low-income housing and in which replacement units are better – e.g., more energy efficient; in better locations for transportation, jobs, or schools; and/or better for reducing racial or ethnic concentrations of poverty.

-

Sale of the property is “appropriate” for reasons consistent with the PHA’s goals, the PHA Plan, and the purpose of the Public Housing Act - a vague option for disposition applications.

Resident Relocation Provisions

The demo/dispo application must have a relocation plan that states:

-

Demolition or disposition cannot start until all residents are relocated.

-

Residents will receive 90 days’ advance notice before being relocated.

-

Each household must be offered comparable housing meeting housing quality standards (HQS) and located in an area that is not less desirable.

-

Residents’ actual relocation expenses will be reimbursed (but the Uniform Relocation Act, URA, does not apply).

Voluntary Conversion

A PHA may convert any public housing development to vouchers under Section 22 of the Housing Act of 1937. A PHA must first send HUD a “conversion assessment” and then a “conversion plan.” A special HUD office is in charge, the Special Applications Center, SAC. (This is different from Section 33, which is about “required” conversions of public housing that have high vacancy rates and would be too expensive to repair over the long-run.)

Conversion Assessment

The first step a PHA must take to voluntarily convert public housing to vouchers is to conduct an assessment and send it to HUD as part of a PHA’s next Annual PHA Plan. The assessment must address five factors:

-

Cost. What is the cost of providing vouchers compared to the cost of keeping units as public housing for the remainder of the property’s useful life?

-

Market Value. What is the market value before rehabilitation if kept as public housing compared to conversion to vouchers, and what is the market value after rehabilitation if kept as public housing compared to conversion to vouchers?

-

Rental Market Conditions. Will residents be able to use a voucher? A PHA must consider:

-

The availability of decent, safe, and sanitary homes renting at or less than the PHA’s voucher payment standard.

-

The recent rate of households’ ability to rent a home with a voucher.

-

Residents’ characteristics that might affect their ability to find and use a voucher; e.g. are there homes accessible to people with disabilities or homes available in the right sizes for families.

-

-

Neighborhood Impact. How would conversion impact the availability of affordable housing in the neighborhood and the concentration of poverty in the neighborhood?

-

Future Use of the Property. How will the property be used after conversion?

Three Conditions Needed for HUD Approval of Conversion. The assessment must show that converting to vouchers:

-

Will not cost more than continuing to use the development as public housing.

-

Will principally benefit the residents, the PHA, and the community. The PHA must consider the availability of landlords willing to accept vouchers, as well as access to schools, jobs, and transportation. The PHA must hold at least one public meeting with residents and the resident council, at which the PHA explains the regulations and provides draft copies of the conversion assessment. Residents must be given time to submit comments. The assessment sent to HUD must summarize residents’ comments and the PHA’s responses.

-

Will not have a harmful impact on the availability of affordable housing.

Conversion Plan

- Description of the conversion and future use of the property.

- Analysis of the impact on the community.

- Explanation showing how the conversion plan is consistent with the assessment.

- Summary of resident comments during plan development and the PHA’s response.

- Explanation of how the conversion assessment met the three conditions needed for HUD approval (as listed above).

- Relocation plan that:

- Indicates the number of households to be relocated, by bedroom size and by the number of accessible units.

- Lists relocation resources needed, including:

- The number of vouchers the PHA will request from HUD.

- Public housing units available elsewhere.

- The amount of money needed to pay residents’ relocation costs.

- Includes a relocation schedule.

- Provides for a written notice to residents at least 90 days before displacing them. The notice must inform residents that:

- The development will no longer be used as public housing and that they may be displaced.

- They will be offered comparable housing that could have tenant-based or project-based assistance, or be other housing assisted by the PHA.

- The replacement housing offered will be affordable, decent, safe, and sanitary, and is housing that the household chooses (to the extent possible).

- If residents will be assisted with vouchers, the vouchers will be available at least 90 days before displacement.

- Relocation and/or mobility counseling might be provided.

- Residents may choose to remain at the property with a voucher if after conversion the property is used for housing.

Resident Participation

The conversion plan must be sent to HUD as part of a PHA’s next Annual PHA Plan within one year after sending the conversion assessment. The conversion plan can be sent as a Significant Amendment to an Annual PHA Plan.

In addition to the public participation requirements for the Annual PHA Plan, a PHA must hold at least one meeting about the conversion plan with residents and the resident council of the affected development. At the meeting the PHA must explain the regulations and provide draft copies of the conversion plan. In addition, residents must have time to submit comments, and the PHA must summarize resident comments and the PHA’s responses.

Conditions Needed for HUD Approval of a Conversion Plan. A PHA cannot start converting until HUD approves a conversion plan. Conversion plan approval is separate from the HUD approval of an Annual PHA Plan. HUD will provide a PHA with a preliminary response within 90 days. HUD will not approve a conversion plan if the plan is “plainly inconsistent” with the conversion assessment, there is information and data that contradicts the conversion assessment, or the conversion plan is incomplete or fails to meet the requirements of the regulation.

The Roadblock: The Faircloth Amendment

Senator Lauch Faircloth of North Carolina successfully placed a harmful amendment into the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act in 1998. The new law made several administrative changes to HUD programs, adding several provisions making life in public housing harder on residents. The act established minimum rents and created a community-service volunteering requirement for public housing residents not already working or participating in a self-sufficiency program.

The “Faircloth Amendment” was the most counterproductive part of this troubling public housing law. The amendment bans PHAs from increasing the number of public housing units in their communities. Of course, funding for public housing has been so limited that most PHAs would not have been able to proceed with expansions even if they wanted to, but no efforts to expand public housing in the future can occur until Congress repeals Faircloth.