Each year, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) measures the availability of rental housing affordable to extremely low-income households and other income groups. Based on the American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS), The Gap presents data on the affordable housing supply and housing cost burdens at the national, state, and metropolitan levels. The report also examines the demographics, disability and work status, and other characteristics of the extremely low-income households most impacted by the national shortage of affordable and available rental homes.

Who Are the Lowest Income Renters?

Of the 45.6 million renter households in the United States, 10.9 million have extremely low incomes – that is almost 1 in every 4 renters who have incomes at or below either the federal poverty guideline or 30% of the area median income (AMI), whichever amount is higher.

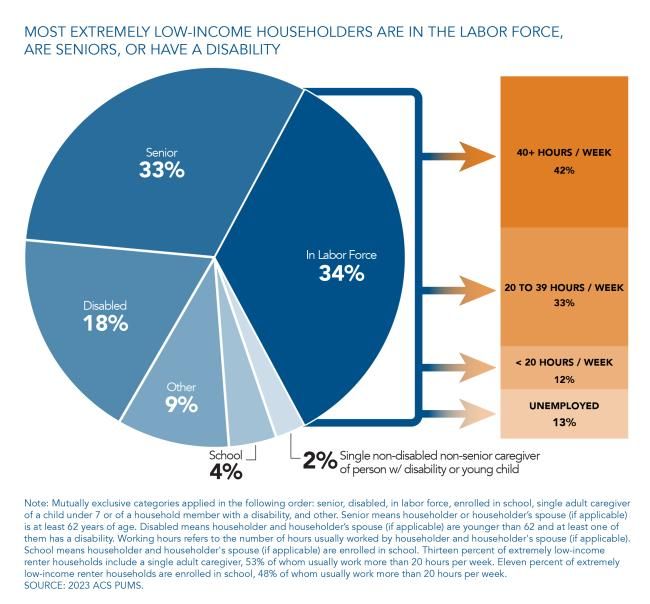

Fifty-one percent of renter householders with extremely low incomes are seniors or householders with disabilities. Another 40% are in the labor force, in school, or single-adult caregivers of school-aged children or family members with disabilities. Of those in the labor force, 42% usually work 40 or more hours per week.

The shortage of affordable and available rental homes disproportionately affects Black, Latino, and Indigenous households, as these households are both more likely to be renters and to have extremely low incomes. Black households are nearly three times as likely and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native households are more than twice as likely as white households to be extremely low-income renters. Eighteen percent of Black households, 17% of American Indian or Alaska Native households, and 13% of Latino households are extremely low-income renters, compared to just 6% of white households. This disparity is the product of historical and ongoing injustices that have systematically disadvantaged people of color, contributing to lower homeownership rates, income, and wealth accumulation.

There Is a Severe Shortage of Affordable Housing for the Lowest-Income Renters

The U.S. has a shortage of 7.1 million rental homes affordable and available to renters with extremely low incomes. Only 35 affordable and available rental homes exist for every 100 extremely low-income renter households nationally. The shortage of affordable and available homes for extremely low-income renters impacts all states and the 50 largest metro areas, none of which have an adequate supply for the lowest-income renters. Among states, the supply of affordable and available rental homes ranges from 17 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households in Nevada to 62 in North Dakota. Forty-one of the largest 50 metros have fewer than the national level of 35 affordable and available units for every 100 extremely low-income renters.

The Shortage of Affordable Housing Results in Cost-Burdens and Housing Instability for Millions of Renters

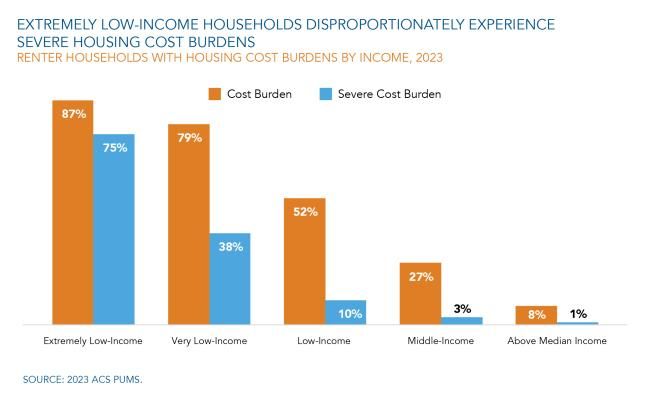

Cost burdens are a direct result of low incomes and the shortage of affordable and available rental homes. A household is cost-burdened when it spends more than 30% of its income on rent and utilities and severely cost-burdened when it spends more than 50% of its income on these expenses. Eighty-seven percent of all extremely low-income renters experience some degree of cost-burden, and 75% are severely cost-burdened. They account for 68% of all severely cost-burdened renter households in the U.S.

Extremely low-income renters who are severely housing cost-burdened tend to have little, if any, money remaining for other necessities after paying rent. A severely cost-burdened extremely low-income family of four with a monthly income of $2,600 paying the average two-bedroom fair market rent of $1,670 spends nearly 64% of their income on rent alone and has only $930 left over each month to cover other necessities. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) "thrifty food budget" for a family of four (two adults and two school-aged children) estimates a family needs to spend $976 per month to cover food costs alone, which is $46 more than their remaining income after paying rent. After rent and food, there is nothing of their income left to cover the costs of transportation, childcare, clothing, and all other necessities.

Addressing the Shortage

The shortage of affordable housing for the lowest-income renters documented in The Gap is systemic and rooted in limitations of the private market. What extremely low-income renters can afford to pay for rent does not cover the development and operating costs of new housing, and it often is not sufficient to provide an incentive for landlords to maintain older, lower-cost housing. The result is that the private market, on its own, fails to provide an adequate supply of affordable housing for the lowest-income renters in nearly every community. Public subsidies are needed to produce new affordable housing, preserve existing affordable housing, or subsidize the difference between what the lowest-income renters can afford to pay and market rents. Yet Congress chronically underfunds affordable housing programs. Only one in four renters who qualify for housing assistance receive it.

Despite staggering affordability challenges and underfunded housing assistance, there are efforts to drastically cut housing assistance programs and the agencies, like HUD, that administer them. Congress should reject these efforts by expanding bipartisan investments in housing assistance programs. Greater investments in the national Housing Trust Fund and public housing would go a long way to preserve and expand the supply of deeply affordable housing, while increases in Housing Choice Vouchers would help reduce the gap between incomes and market rents. Congress should also ensure adequate staffing at the agencies responsible for the efficient administration of our housing assistance programs.