Renovated former tobacco warehouses near downtown Durham, North Carolina

There are many definitions for gentrification, which can make discussions about development and displacement confusing.

Many anti-displacement activists define gentrification as a profit-driven, race, and class change of a historically disinvested neighborhood. “Disinvested” in this context means areas that businesses and governments have abandoned—where there has been little new development or maintenance of existing buildings or institutions. Gentrification occurs where land is cheap and the chance to make a profit is high due to the influx of wealthier wage earners willing to pay higher rents.

One case of extreme gentrification is the Bay Area in California, which is undergoing a radical makeover due to the rise in technology companies replacing old industries and jobs. New people moved in to work for these companies and replaced the pre-existing residents. Land values and housing prices increased dramatically, as did the pressure for property owners to get the most out of rents on urban spaces. The Bay Area has become the second densest urbanized area in the country after Los Angeles.

The Bay Area has grown radically wealthier, but the newfound wealth coming from the tech, medicine and finance businesses goes to a small percentage of people. (The area has more millionaires and billionaires than New York City.) The upper layers of the labor force are getting paid very well, allowing them to outbid ordinary working people, the elderly, and people with disabilities for homes. This increased competition for housing has left areas like Oakland and the San Francisco Mission less affordable for long-term residents.

Race is tied to class and power in gentrification. Most of the wealthy and well-paid in the Bay Area are white while those being displaced are people of color, who typically have less income to bid for housing and are more often renters at greater risk of eviction. The elite can hold onto their claims to the city because they also hold the political power.

There are ways, however, to revitalize neighborhoods without also gentrifying them. One is to use a positive development model that builds a new vision of community health and sustainability that benefits all residents. Community organizing that brings different groups to the same table to identify a shared interest and common struggle is key to ensuring development that empowers entire communities.

The development process should enable community members to identify the types of housing, services and infrastructure that should exist in their neighborhood. The process should value longtime residents’ visions of neighborhood change and give the power of decision-making to community residents. A healthy community is one that acknowledges and supports the importance of racial equity, community and culture.

Public agencies can foster positive development by supporting a shared neighborhood vision and working with community institutions to ensure a successful revitalization that values culture, health, and positive human development, not just increased economic activity. Agencies should help ensure lasting change though development without displacement.

Advocates from United for a New Economy – Denver, Colarado

Credit: John Goldstein

Displacement — The Real Enemy

The most common problem people associate with gentrification is the displacement of residents from a neighborhood experiencing redevelopment. Displacement happens in various ways. “Direct displacement” is when residents are forced to move because of rent increases and/or building renovations. “Exclusionary displacement” is when housing choices for low-income residents are limited. “Displacement pressures” are when supports and services that low-income families rely on disappear from the neighborhood.

Although displacement is cited as the most common concern of gentrification, the research on gentrification and displacement is unclear. Ingrid Gould Ellen and Gerard Torrats-Espinosa studied the long-term effects of gentrification and tracked racial change over time. They defined gentrification narrowly as an increase of income in a neighborhood compared to the larger metro region over time.

The researchers found that a growing number of low-income neighborhoods occupied predominantly by people of color have gentrified in recent decades, although most have remained low-income. Gentrification in the short-term has brought racial integration for many of these neighborhoods, and neighborhoods that became racially diverse through gentrification remained racially diverse past the initial gentrification period. Some neighborhoods that experienced gentrification in the 2000s, however, did experience a more significant rise in white population in the short term and may not experience the same racial stability in the long term.

Gentrification can also benefit neighborhood residents by lowering poverty rates and exposing residents to more opportunity. Recent studies found that public housing residents in gentrifying neighborhoods are exposed to less violent crime, are more often employed, and have higher incomes and greater educational attainment than their counterparts in low-income neighborhoods. Urban revitalization also brings more services to an area. A lack of choice and competition in disinvested neighborhoods may cause families to pay more for goods and services. There can be benefits to gentrification, but only to long-term residents who are not pushed out. Development without displacement is the key. Fighting against displacement rather than fighting against development should be the focus.

An exclusionary effect of gentrification is the high cost of rents that force low-income households to move to lower-cost neighborhoods with fewer resources. Displaced low-income households most likely end up in new low-income neighborhoods. Many vulnerable households that do move are renters and are at greater risk of moving to neighborhoods that have lower home values, high unemployment rates, lower median incomes and poor public-school performance.

Cultural displacement is also common. The closing of long-time neighborhood landmarks like historically black churches or local restaurants can erase the history of a neighborhood and with it a sense of belonging. The influx of a new population of upper- and middle-income residents can also change the political landscape, with new leaders ignoring the needs of long-time residents. The loss of long-time residents’ political power leads to further withdrawal from public participation and a loss of control.

Although gentrification can bring about racial diversity, integration, neighborhood improvements, and greater access to services, advocates need to actively promote policies that protect tenants from displacement. Preserving the subsidized housing in gentrifying neighborhoods can ensure that income and racial diversity remains in a neighborhood over time. Governments should also create more affordable low-income homes in gentrifying neighborhoods through new construction and acquisition. Housing subsidies should require long-term or permanent rather than temporary affordability. The next section of Tenant Talk will explore these solutions in more detail.

Local Policy Solutions for Preventing Displacement

Grace Townhomes formed by the Community Justice Land Trust. Photo: Domus, Inc

The data on displacement due to gentrification is insufficient. Many researchers have measured the problem at the city or metro level, but there are few studies that look at neighborhood or “submarket” areas. There is also not a silver bullet or list of sure-thing policies to prevent displacement, but the following are some of many tools that can help combat gentrification. They include baseline protections for the most vulnerable residents, producing and preserving affordable homes, non-market-based approaches to housing and community development, and approaches to community participation.

Community Land Trusts

One of the biggest problems with gentrification is land. Developers and investors buy land when it is affordable in struggling neighborhoods, and then wait for the right moment to move forward with profitable development. Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are one way to keep land owned by the community and to fight against rapid property value escalation.

CLTs are nonprofits that own land - received as donations or bought with government subsidies - to ensure it stays affordable for long periods. The land is used for housing or other community purposes. If it’s for housing, the homes are sold to lower-income families, but the land is still owned by the CLT. When a CLT homeowner moves, they sell the home back to the CLT or another low-income family. The CLT homeowner receives a more modest return on their investment than a regular homeowner when they sell because they “share equity” (the land portion) with the CLT.

Some concerns with CLTs are that they are costly to implement (require substantial funding), especially in gentrifying neighborhoods, and they rarely provide homes to extremely low-income families. CLTs also usually operate on a small scale, which could be helped if cities gave public land to CLTs and established supporting organizations to build them.

The Community Justice Land Trust (CJLT) in Philadelphia, PA, was created in 2010 by a community coalition that included the Women’s Community Revitalization Project (WCRP) and the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations. Philadelphia CJLT addresses the community’s recent dramatic increases in housing prices, the rise in new development that did not consider existing needs, and the problem of vacant land and abandoned buildings. The land trust has 36 rent-to-own townhomes and plans to develop 75 more. It is governed by an advisory committee of residents and other stakeholders, as well as WCRP board members.

Research on one of the largest CLTs in the U.S.—Champlain Housing Trust in Vermont —shows that lower-income affordability continued and improved between generations of homebuyers, homeownership was expanded for persons left out from the market, most homeowners gained wealth, and most homeowners bought market-rate homes after they left the CLT. Though CLTs provide limited opportunities for the homeowners to build wealth, they help sustain relative affordability for lower-income households over time.

Rent Control

Rent-control policies offer protections from sudden rent increases, establish maintenance standards, provide the right to a lease renewal, provide the framework for organizing and litigation, and set limits on security deposits. These policies directly affect neighborhood affordability by preventing rents from skyrocketing, enabling residents to stay in their apartments for the long term. Basically, rent control sets a cap on how much a landlord can charge for the rent.

New York Housing March, January 2018. Photo: Ethan Fox

New York has the strongest rent-control policies in the U.S. The Emergency Tenant Protection Act (ETPA) of 1974 established details for rent control and allowed eight counties to voluntarily participate. Currently, 966,000 apartments (45% of the rental market) are rent-stabilized in New York. Since the 1990s, when the law was weakened, the state has lost 300,000 units of rent-stabilized housing. Landlords can remove apartments from rent control when a renter vacates the apartment and then make substantial improvements. This loophole has led landlords to harass, frighten or incentivize renters into leaving their rent-regulated homes.

The ETPA is due to expire in 2019. The Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance sees this as an opportunity to strengthen and expand tenants’ rights and is calling for the state to undo provisions that incentivize the loss of rent-regulated units and to extend the rent stabilization framework to the entire state.

Rent-control policies must be carefully implemented to avoid negative consequences. First, rent controls are not tied to specific residents, so there is no way to ensure they are benefiting the people most in need; there are many examples of higher-income, even wealthy, people benefitting from rent control while extremely low-income people remain homeless or on housing assistance wait lists. Second, landlords and developers regularly attack rent control laws, so a strong advocates’ rights coalition is needed to ensure proper enforcement and to advise renters on seeking legal recourse. Third, landlords often argue that legal cap on rents leave them too little income for repairs and maintenance, so rent control policies must be paired with enforceable building standards.

Just-Cause Eviction Ordinances

Every rental lease has an end date, even those made by spoken agreement. It is common that when a lease expires, it automatically renews month-to-month on the same terms as the previous lease. Many renters are displaced because at the end of any given lease term, the landlord can simply “not renew” the contract. Some jurisdictions prevent such displacement by passing “Just-Cause” eviction ordinances stipulating that a landlord cannot evict a renter unless there has been a specific violation of the lease. Non-renewal is no longer an option.

Seattle, WA, has had a just-cause eviction ordinance in place since 1980 that applies to verbal leases and month-to-month leases. In these cases, a landlord may ask a tenant to leave for 18 specific reasons, such as failure to pay rent or renter damage to the property.

Just-cause eviction protections are most effective when paired with rent control. If there is no limit on the amount a landlord can increase the rent, a landlord often can just double the rent, and effectively push the renter into moving, without a just cause for eviction.

Community Benefits Agreements

Community benefits agreements (CBAs) are legal contracts signed by a developer and community groups. They spell out the benefits a developer promises to provide to the community as part of a development. CBAs give community groups a voice in shaping projects and the legal authority to enforce developers’ promises.

For CBAs to be effective, they need to be created by active community-based coalitions willing to stay involved during the development process to hold the developers accountable. Coalitions must ensure any CBAs include fair benefits that are reflective of the community’s wishes. If CBAs are weak, they cannot be changed and can be used by developers to look good in the public eye without delivering substantive benefits.

"CBAs give community groups a voice in shaping projects and the legal authority to enforce developers’ promises."

Cherokee Denver had purchased the Gates rubber factory in Denver, CO, in 2001 to redevelop the site. They worked with the community to create a CBA that included affordable homes and job guarantees, but the project fell through because of the recession. Broadway Station Partners (BSP) finally bought the land in 2018 to create a mixed-use development. The community surrounding the factory site formed a CBA with BSP, similar to the now-repealed Cherokee Gates Urban Redevelopment Plan. BSP agreed to build 338 affordable homes (affordable for 40 years) and to hire local construction workers. This strong CBA required community groups to stay engaged with developers over nearly 20 years to ensure that redevelopment would have community interests at heart.

Gates Rubber Factory. Photo: John Goldstein

Tenant Option to Purchase

“Tenant option to purchase” (TOP) is a tool for residents facing eviction because the property owner intends to sell the property, demolish it, or convert to another use. Cities can pass a TOP policy to require that any housing unit undergoing such changes is offered to residents first before being sold, demolished or re-rented on the private market. The benefits of TOP policies are that they create legal rights for individuals and families faced with displacement, they can ensure housing stability for existing tenants by giving them an option to return to their original homes after being relocated, and they can increase living standards that benefit the existing tenants.

The District of Columbia has an effective Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). This law requires owners of properties with two or more rental units give tenants and/or tenant associations the option to buy the apartments before a property conversion takes place. If the owner does not provide tenants the option to purchase, the tenants can pursue a lawsuit against the owner. According to Scott Bruton at the Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development, TOPA is the most valuable tool the District has for preserving affordable rental housing. Without TOPA, affordable housing developers would lose out to for-profit, market-rate developers in buying multifamily rental properties.

Regulating and Taxing Short-Term Rentals

Research shows that short-term rentals correlate with fewer regular rental units (each unit that gets converted to a short-term rental, takes one away from renters), increased rents, and higher property values, which all lead to displacement. Jurisdictions could regulate and tax the short-term rental operators, many of whom work through AirBnB. Jurisdictions could limit the number of days per year a room or apartment can be rented short-term, require a local contact person be licensed for short-term rentals and fine offenders, and require that only apartments occupied by a permanent resident who is leaving temporarily may be rented short-term.

Taxing short term rentals is another option. Citizen’s Housing and Planning Association (CHAPA) advocates were successful in getting a state law passed that applies the 5.7 % hotel and motel room tax to short-term rentals (effective July 1, 2019), excluding homeowners who rent their units for two weeks or less during the year. At least 35% of the revenue generated must fund affordable housing, the first state to do so. The law also allows jurisdictions the authority to create additional local taxes, makes short-term renters obtain $1 million in liability insurance, and creates a public registry of short-term rentals. It remains to be seen whether this bill, the first of its kind, prevents the future loss of affordable homes.

"The benefits of TOP policies are that they create legal rights for individuals and families faced with displacement..."

Vacancy Taxes

Rents rise when there is insufficient housing for all who need it. Vacant properties, of course, provide no housing. Some real estate investors buy buildings and let them sit empty – a phenomenon called “speculation” - often in areas at risk of gentrification where land can be relatively cheap. Real estate investors buy the property and allow it to sit empty because that costs less than managing the building and making sure it’s up to local codes. When the right development opportunity arises, they sell the property or demolish it to make way for something new.

In some communities, speculation has led to a rapid growth in vacant apartments, and some jurisdictions have begun taxing property owners who refuse to make homes available for rent. Voters in Oakland, CA, passed such a tax law by a vote of 68%-31%. The new tax will generate about $10 million annually, which will the city will then invest in affordable housing.

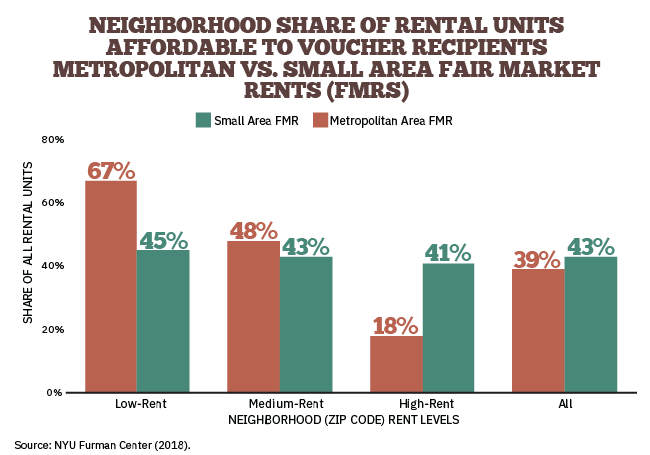

Small Area Fair Market Rents Can Help Minimize Harm Due to Gentrification

Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs) are a potential tool to minimize displacement of residents and help ensure an income mix in gentrifying neighborhoods.

What are Small Area FMRs?

SAFMRs base the value of a Housing Choice Voucher to a landlord on rents in a ZIP Code. Without SAFMRs, the value of a voucher is based on Fair Market Rent (FMR), which is based on rents in an entire metro area. Metro areas have many areas with very different market rents. A voucher pays the difference between 30% of a household’s income and the voucher “payment standard.” Public housing agencies (PHAs) set a payment standard (the amount a landlord gets from a voucher) at 90% to 110% of the FMR. As a result, the FMR voucher value is often not enough for rents in gentrifying neighborhoods.

Use of SAFMRs ensure payment standards (the value of vouchers) are more in line with neighborhood rental markets, making vouchers more valuable in higher-rent neighborhoods, such as those undergoing gentrification. Vouchers that pay less that the market rate make it difficult to rent in gentrifying neighborhoods. Household often end up paying more than 30% of their income for rent (paying the difference between the voucher payment and landlord’s market rent).

Minimizing Displacement and/or Fostering Mixed-Income Neighborhoods

Where SAFMRs are available, long-time residents with vouchers (or voucher applicants) living in gentrifying neighborhoods might be able to remain in their homes, avoiding displacement as landlords attempt to cash in on rising demand for rental housing. Use of SAFMRs before a neighborhood fully gentrifies can help new income-eligible households move into a neighborhood to take advantage of the improving community features and provide a healthy mixed-income area.

Required and Voluntary SAFMRs

A new HUD regulation required PHAs in 24 metro areas to begin using SAFMRs on April 1, 2018. SAFMRs have to be used by all PHAs in those metro areas, not just the PHA in the major city – e.g., 19 PHAs in the Philadelphia metro area must use SAFMRs, not just the Philadelphia PHA. More metro areas could be required to use SAFMRs in the future. PHAs anywhere can voluntarily use SAFMRs, and residents should advocate for their PHAs to use them. A list of the 24 metro areas can be found at: https://bit.ly/2Vt3KLq

One issue, however, is that landlords are not required to rent to households with vouchers. There are two categories of exceptions:

- Landlords must accept vouchers if their building is assisted by the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, HOME, or national Housing Trust Fund programs.

- Some cities and states have laws that ban “source-of-income” (SOI) discrimination, prohibiting landlords from refusing to rent paying with a voucher, Supplemental Security Income, or Social Security. The Poverty & Race Research Action Council annually updates a list of SOI laws at: https://bit.ly/2DKnFQ0

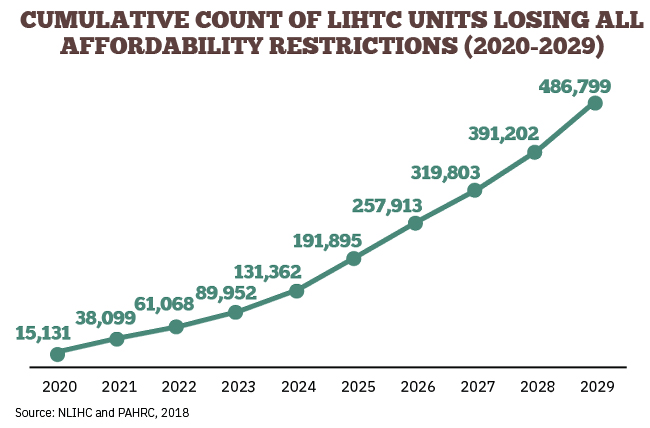

Extended Affordability Requirements are a Tool to Preserve Affordable Housing

The lowest-income renters face a national shortage of more than seven million affordable, accessible and available rental units, and only one in four eligible low-income renters receives the assistance they need. The affordable housing crisis could worsen when 279,207 publicly subsidized rental homes reach the end of their affordability periods over the next five years; these homes could convert to market-rate rents without additional subsidy. One way to prevent future losses of affordable homes is to extend affordability requirements.

Many state legislatures have chosen to extend the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) housing affordability requirements beyond the year 30 limit. LIHTC is the largest federal affordable housing production in the U.S., and many LIHTC homes risk being converted to market rate housing once affordability restrictions expire. The states with extended mandatory affordability requirements include Pennsylvania, Florida, Vermont, Maine, New Hampshire, Oregon, Utah, Hawaii, Colorado, Maryland, and Connecticut*. Most of these states have affordability requirements of 35 to 50 years; they are 60 years in Oregon, 99 years in New Hampshire, and permanent in Vermont.

Vermont’s permanent affordability requirement was created in the 1980s because many affordable homes built with HUD and USDA funding had affordability requirements expiring at that time. Many property owners chose to convert the affordable units to market-rate housing, leading to a massive displacement of the lowest-income renters. At the same time, HUD was reducing affordable housing subsidies available to state and local governments.

The “Vermont Housing and Conservation Trust Fund Act in 1987” requires any housing subsidized by the state must be permanently affordable to lower-income Vermonters. Compliance is monitored by a community-based nonprofit or a public agency like the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board (VHCB). Over the past thirty years, VHCB has assisted nonprofits and municipalities develop 8,300 permanently affordable homes. In addition to homes made permanently affordable, VHCB prevented virtually all affordable homes built with HUD and USDA subsidies from turning into market-rate housing.

Solutions like permanent or extended affordability requirements protect the limited supply of affordable homes, which in turn can effectively ensure low-income residents remain in their neighborhoods. NLIHC advocates for the longest possible affordability periods in all federal programs, and while progress is slow, advocates can win extended or permanent affordability requirements for states or cities’ uses of federal dollars!

Opportunity Zones—A Potential New Challenge in the Fight against Gentrification

The “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017”—President Trump’s massive tax cut law that mostly benefits wealthy Americans and corporations — created “Opportunity Zones,” 8,700 ZIP codes where governors have determined a need for more investment and where those who do invest will now receive significant tax benefits.

The Opportunity Zones (OZ) concept—more investment in struggling neighborhoods — could be a good thing. Senators Tim Scott (R-SC) and Cory Booker (D-NJ), who authored the plan, hope to address blight and crumbling infrastructure. As passed, however, the law does not incentivize, much less require, the investments be used to benefit long-term residents by building affordable housing, supporting local businesses, creating decent-paying jobs, or providing other types of community benefits. Investor-developers can now receive large federal tax benefits to build anything from hotels to luxury condos to corporate office buildings, as long as they build it in an OZ.

Housing Trust of Rutland County makes renovations to Heritage Courts in Poltney, VT

To compete for a governor’s OZ designation, a ZIP code had to have a poverty rate of at least 20% or a median income no greater than 80% of the area median income. ZIP codes can be quite large, include a variety of income groups, and contain wealthy pockets or a major university or an arts district in an otherwise poor area. Also, not all OZ ZIP codes need to meet the “low-income” definition; up to 5% of the OZs can include ZIP codes next to a “low-income” ZIP code, as long as the adjacent ZIP code has a median income no more than 125% of the low-income ZIP code. All of the OZ investment activity could happen in the wealthier ZIP code, with little or no benefit to the neighborhoods in need.

Combating this new gentrification pressure will require advocates to engage with local officials approving the developments. Advocates should argue that proposed projects in OZs must include permanently affordable rental housing. Advocates must also urge their members of Congress in Washington, DC, to call upon the Department of Treasury to issue strong and clear regulations for OZ investments that require a focus on extremely low-income people, increase affordable rental housing, and support the neighborhood development vision of long-term residents.

"Combating this new gentrification pressure will require advocates to engage with local officials approving the developments."

Some have merely asked for “transparency” by requiring OZ administrators to report outcomes – an after-the-fact exercise. Without strong regulations at least providing incentives, if not requirements, that protect long-term residents from displacement and ensure real benefits to low income communities, the reporting will be an empty exercise.