About the Report

For more than 35 years, the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s (NLIHC) Out of Reach report has called attention to the disparity between wages and the cost of rental housing in the U.S. Every year the report has shown that affordable rental homes are out of reach for millions of low-wage workers, seniors, families, and other renters. The report’s central statistic, the Housing Wage, is an estimate of the hourly wage a full-time worker must earn to afford a modest rental home at HUD’s Fair Market Rent (FMR) without spending more than 30% of their income on housing costs – the accepted standard of affordability. The FMR is an estimate of what a family moving today can expect to pay for a modestly priced rental home in a given area.

Housing is Out of Reach

In 2025, a full-time worker needs to earn an hourly wage of $33.63 to afford the average modest, two-bedroom rental home in the U.S. and $28.17 to afford a modest one-bedroom rental home. The federal minimum wage of $7.25 falls far short of either wage. Even after factoring in higher state and local minimum wages, the average minimum-wage worker in the U.S. must work 116 hours per week (2.9 full-time jobs) to afford a two-bedroom rental home at Fair Market Rent, or 97 hours per week (2.4 full-time jobs) to afford a one-bedroom rental home at the Fair Market Rent. In no state, metropolitan area, or county in the U.S. can a full-time worker earning the federal minimum wage, or the prevailing state or local minimum wage afford a modest two-bedroom rental home at Fair Market Rent.

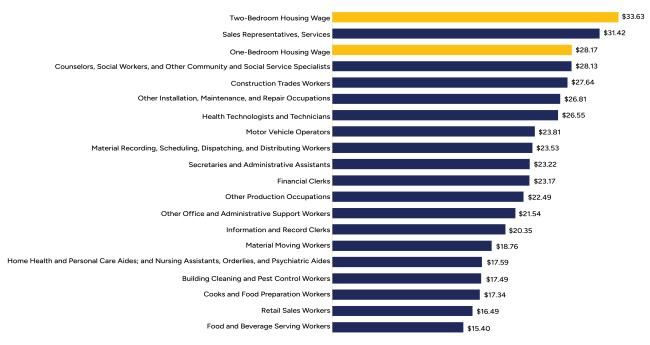

The affordability crisis affects more than just minimum wage earners. The average hourly wage earned by renters is $23.60 in 2025, which is $10.03 less than the national two-bedroom Housing Wage and $4.57 less than the one-bedroom Housing Wage. In 49 states, the average renter wage is not enough to afford a two-bedroom rental at Fair Market Rent. In 37 states, it falls short of affording even a one-bedroom rental. Even workers in the nation’s most common occupations struggle to afford housing. Of the 25 most common jobs in the U.S., 17 pay median wages that fall below the Housing Wage for a one-bedroom rental and 18 pay below the two-bedroom Housing Wage. These 18 occupations employ approximately 74 million people—48% of the entire U.S. workforce.

17 of the 25 Most Common Occupations in the United States Pay Median Wages Less Than the One- and Two-Bedroom Housing Wages

• Two-Bedroom Housing Wage – $33.63

• Sales Representatives, Services – $31.42

• One-Bedroom Housing Wage – $28.17

• Counselors, Social Workers, and Other Community and Social Service Specialists – $28.13

• Construction Trades Workers – $27.64

• Other Installation, Maintenance, and Repair Occupations – $26.81

• Health Technologists and Technicians – $26.55

• Motor Vehicle Operators – $23.81

• Material Recording, Scheduling, Dispatching, and Distributing Workers – $23.53

• Secretaries and Administrative Assistants – $23.22

• Financial Clerks – $23.17

• Other Production Occupations – $22.49

• Other Office and Administrative Support Workers – $21.54

• Information and Record Clerks – $20.35

• Material Moving Workers – $18.76

• Home Health and Personal Care Aides; and Nursing Assistants, Orderlies, and Psychiatric Aides – $17.59

• Building Cleaning and Pest Control Workers – $17.49

• Cooks and Food Preparation Workers – $17.34

• Retail Sales Workers – $16.49

• Food and Beverage Serving Workers – $15.40

Source: NLIHC calculation of weighted-average HUD Fair Market Rent. Occupational wages from May 2024 BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, adjusted to 2025 dollars. Note: The BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics excluded Colorado in 2024 due to data quality issues.

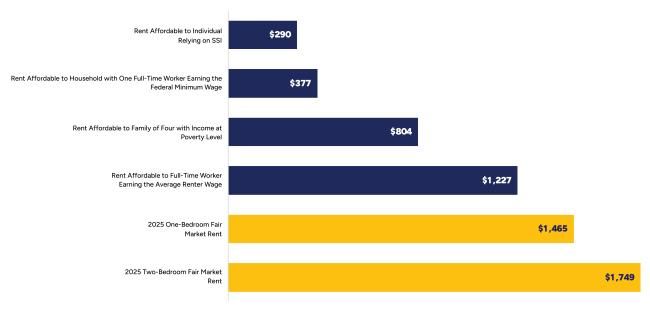

Many low-income renter households include seniors, people with disabilities, students or single-adult caregivers. Because of their situations, they often can’t work or must rely on fixed incomes below the poverty level, or on low- or minimum-wage jobs. In most areas of the U.S., a family of four at the poverty line can afford no more than $804, and many can actually afford less. A full-time worker earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 can afford only $377 per month. Individuals with disabilities relying on federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) can afford only $290 per month. The average monthly Fair Market Rents for one-bedroom home is $1,465 and for two-bedroom homes $1,749, far out of reach for low-income renters in most situations.

Rents are Out of Reach

Source: NLIHC calculation of weighted-average HUD Fair Market Rent. Affordable rents based on income data from BLS QCEW, 2024 adjusted to 2025 dollars; and Social Security Administration, 2025 maximum federal SSI benefit for individual.

The Federal Policies Needed to End the Housing Crisis

Amidst the current economic uncertainty, which represents a potential threat for renters, federal subsidies become even more crucial for addressing the already deep and systemic shortage of affordable housing available to the nation’s lowest-income renters. Yet rather than expanding vital programs, recent federal legislative proposals threaten to slash funding, impose harmful restrictions, and undo years of hard-won progress. To truly address this crisis, Congress must not only protect existing housing programs but significantly strengthen them through sustained investment in the affordable housing stock, expanded rental assistance, and policies that eliminate barriers to housing access.

First, Congress must invest in solutions to expand and preserve the supply of affordable housing. This includes expanding the national Housing Trust Fund to build and preserve affordable housing, as well as investing directly in public housing capital repairs. Second, Congress should expand access to rental assistance to every eligible household in need. Universal rental assistance could be achieved by fully funding the Housing Choice Voucher program. Third, Congress must strengthen and enforce renter protections. These protections include providing legal counsel to renters facing eviction and prohibiting the reporting of rental debt on consumer reports. Renter protections are also needed to ensure homes are safe, healthy, and accessible. Fourth, Congress needs to create a permanent national housing stabilization fund to provide financial assistance to families who experience a sudden and temporary financial setback.

Looking ahead, the future of federal housing assistance is at risk, leaving low-income renters most vulnerable in the face of a potentially unstable economy. The FY25 HUD budget underfunded the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, potentially leading to the loss of 32,000 vouchers. Making matters worse, the President's FY26 budget request proposed a devastating 44% cut to HUD. The American public must reject these harmful budget cuts and instead insist that Congress make sustained, long-term investments in affordable housing programs that will ensure the lowest-income renters can access and maintain safe, stable homes.